1. Introduction: The Silent Conquest of New Worlds

Imagine a lone rover advancing across the red surface of Mars. This isn’t just a remote-controlled vehicle. It’s a robotic pioneer, an explorer relying on autonomous rover navigation to make critical decisions hundreds of millions of kilometers away from any human operator.

But why this complexity? Why not just drive it from Earth with a joystick?

The answer is one word: latency.

Even at the speed of light, a signal sent from Earth takes an average of 13 minutes to reach Mars. A “STOP!” command shouted at the sight of a cliff would take 13 minutes to arrive and another 13 minutes to receive a (tragic) confirmation. 26 minutes in total.

In that time, our rover, like a mindless zombie, would have already plunged into the void.

And the Moon? The situation is apparently better: “only” a 1.3-second delay. But that total “ping” of 2.6 seconds is an eternity. It’s more than enough time to end up in a crater or tip over on a rock before an operator can even react.

The solution, therefore, is autonomy. To explore space, our robots must think for themselves.

This article isn’t just an introduction. It’s the foundational guide to understanding how a rover thinks. It’s the map of the autonomous navigation ecosystem, the starting point from which we will explore every future technology.

Together, we will disassemble a rover’s brain: we’ll see how it builds a map from scratch (SLAM), how it plans the best path (Pathfinding), and how its “reflexes” keep it from crashing (Hazard Avoidance).

Welcome to the silent conquest of new worlds.

2. The “Why”: The Tyranny of Latency

In the introduction, we established a fundamental truth: we cannot drive a rover on another planet with a joystick. The image of the “zombie” rover falling off a cliff isn’t an exaggeration; it’s a physical reality, and the culprit is latency.

In this chapter, we’ll dismantle this concept. We’ll understand that it’s not a simple technical “lag” but a fundamental law of the universe that defines our entire strategy for space exploration. To understand latency is to understand why autonomy isn’t an option, it’s an absolute necessity.

What is Latency? It’s the Speed of Light

If you’ve ever played an online video game with a high “ping,” you’ve experienced latency. It’s that frustrating delay between when you press a button and when your character reacts.

In space, our “connection” is the void, and our signal travels at the fastest speed possible: the speed of light.

The speed of light (denoted as c) is a universal constant, approximately 300,000 kilometers per second (186,000 miles per second). It sounds incredibly fast, but the distances in space are so vast they make it feel almost slow.

The “Tyranny” of latency is this: we cannot go any faster. As Einstein’s theory of relativity teaches us, nothing can travel faster than the speed of light. Every command, every bit of information, must obey this physical law.

The problem isn’t technological; it’s cosmic. We can’t solve it; we can only work around it.

Two Types of Delay: The Moon and Mars

To truly grasp the problem, let’s compare our two most iconic neighbors.

1. The “Fake Friend”: The Moon

The Moon is cosmically close, “only” 384,000 km (about 238,000 miles) away.

- Calculation (One-Way): 384,000 km / 300,000 km/s = ~1.3 seconds

- Round-Trip (A/R): 1.3s (to) + 1.3s (back) = ~2.6 seconds

A 2.6-second delay seems manageable. It’s annoying, but you could almost hold a conversation. But to drive a multi-million-dollar vehicle? It’s lethal.

Imagine driving your car at just 10 km/h (6 mph). In 2.6 seconds, you travel 7.2 meters (23.6 feet). You have all the time in the world to put a wheel in a crater or hit a wall you didn’t see, all before your “STOP!” signal has even left mission control on Earth.

The Moon is a “fake friend” because its low latency tricks us into thinking we’re in control, when in reality, we’re just delayed spectators.

2. The Abyss: Mars

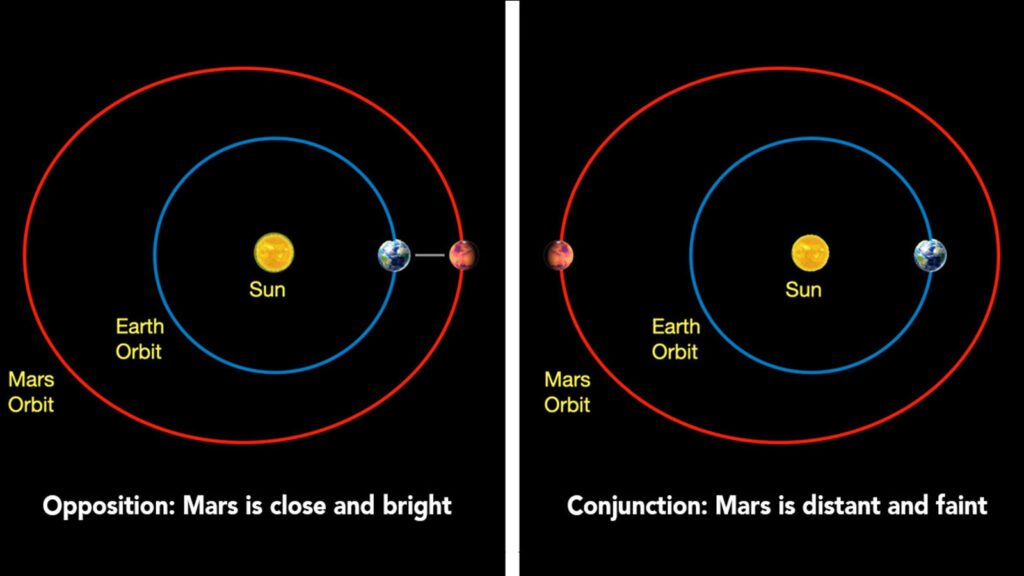

Mars is a completely different game. Unlike the Moon, which orbits us, Earth and Mars both orbit the Sun at different speeds. Their mutual distance is constantly changing.

- At Closest Approach (Opposition): When we are “neighbors,” Mars is about 55.7 million km (34.6 million miles) away.

- Round-Trip Latency: ~6 minutes

- At Farthest Point (Conjunction): When we are on opposite sides of the Sun, Mars is about 401 million km (249 million miles) away.

- Round-Trip Latency: ~44 minutes

The 26-minute example from the introduction is a realistic average.

Think about it: you send the command “turn left.” Half an hour later, you find out if the rover did it and what it saw after turning. In that time, the rover could have gotten stuck in sand, tipped over, or damaged a scientific instrument.

You aren’t driving. You’re sending suggestions and hoping for the best.

How Do We “Call” a Rover?

Now that we understand the delay, let’s see how communication actually happens. It’s not as simple as pointing an antenna and talking. It’s a cosmic dance involving colossal infrastructure on Earth.

The nervous system of interplanetary communication is called the Deep Space Network (DSN), managed by NASA.

The DSN is Earth’s ear (and mouth). It consists of three giant antenna complexes, strategically placed around the world:

- Goldstone, California (USA)

- Madrid (Spain)

- Canberra (Australia)

These locations are separated by approximately 120 degrees of longitude. Why? Because as the Earth rotates, at least one of these stations always has a line of sight to Mars, the Moon, or any other probe in the solar system. They provide nearly 24/7 coverage.

When “we” talk to a rover, Mission Control in Houston or at JPL sends a command. This command is beamed to one of the DSN stations, which “shoots” it toward the planet using enormous parabolic dishes (up to 70 meters or 230 feet wide) to focus the radio signal.

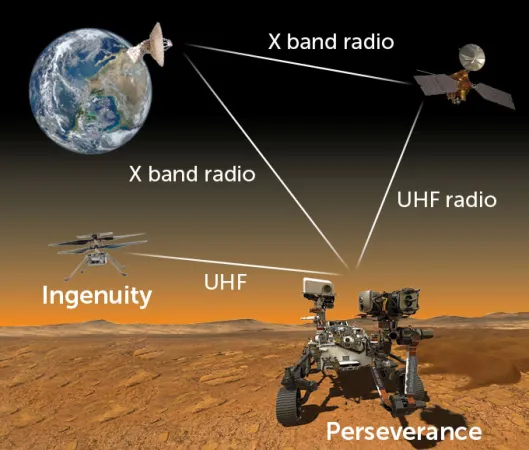

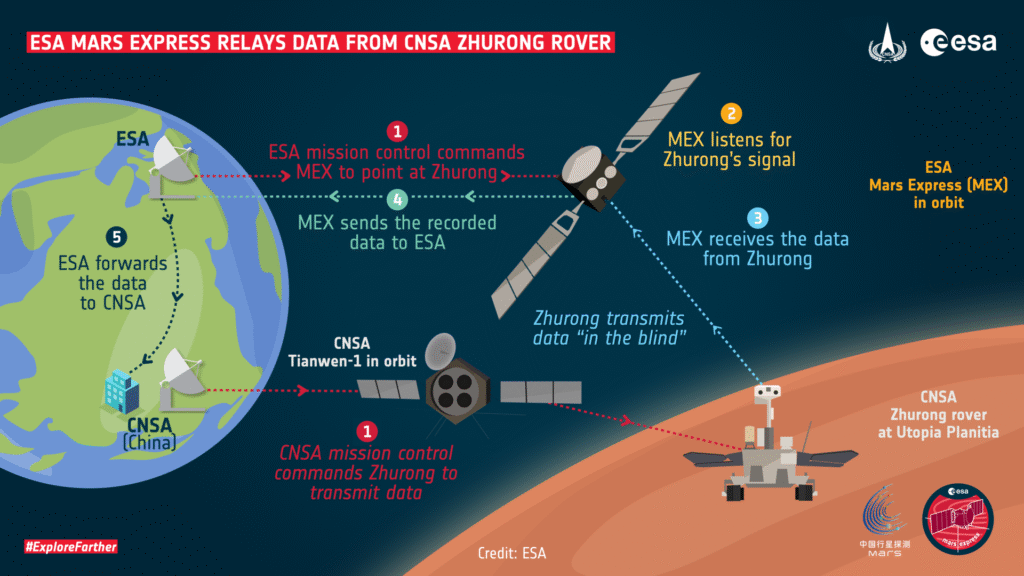

The Orbital “Postman”: Why Rovers Don’t Talk By Themselves

There’s another problem: the signal that reaches Mars is incredibly weak. And the rover itself doesn’t have the power to “shout” a strong signal all the way back to Earth. It has a relatively small antenna and must conserve its precious battery (generated by solar panels or a nuclear RTG) for moving and doing science.

The solution is a two-step system called “Store-and-Forward.”

- From Orbiter to Earth: The orbiter, which is a much larger satellite with huge solar arrays and a powerful antenna, stores the rover’s data. Then, when it has a clear line of sight to Earth, it “forwards” the data packet to the DSN.

- From Rover to Orbiter: The rover (e.g., Perseverance) waits for an “ally” to pass overhead. This is an orbiter, like the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) or the European Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO). The rover sends its data to the orbiter. This is a “local call”: short distance, high bandwidth, low power.

This means the rover can’t even communicate when it wants to. It can only send (and receive) data during the brief “communication windows” when an orbiter is visible in its sky, perhaps 2-3 times per day (or “Sol,” as a Martian day is called).

When the Line Drops: Solar Conjunction and Blackouts

The situation, already complex, can get even worse. There is a period, occurring roughly every two years, called Solar Conjunction.

This is when Mars and Earth are on exact opposite sides of the Sun. The Sun, being an incredibly noisy (radio-electrically) ball of plasma, sits directly between us and the rover.

Any signal sent would be corrupted or blocked by solar interference. For about two weeks, communication is impossible.

During this time, control centers on Earth enter a “command moratorium.” They send nothing.

The rover is completely, totally alone.

It must be smart enough to continue simple tasks (or just put itself in “safe mode”) and, above all, not die. It must know how to manage its own power, its own temperature, and how to stay out of trouble, with no help from home for weeks.

Conclusion: Autonomy is Not a Luxury

As we’ve seen, latency isn’t just a delay. It’s a brick wall imposed by physics.

This wall is compounded by logistical bottlenecks (the orbiters) and total blackouts (solar conjunction).

Robotic exploration faces a choice:

- Stand still, move a few centimeters, wait hours for commands, and do very little science.

- Build a brain.

Autonomy isn’t a “plus” or a luxury feature. It is the only possible solution to the tyranny of latency.

Now that we understand why we can’t drive, in the next chapter, we’ll get into the “What”: the anatomy of that robotic brain. We’ll explore the three pillars that allow a rover to see, think, and move on its own.

3. The “What”: Anatomy of a Robotic Brain 🧠

In the previous chapter, we established an inescapable “Why”: the tyranny of latency. We understood that we can’t drive a rover in real-time. Our only solution is to “Build a brain.”

But what’s inside this brain?

If you open the electronics box of a rover like Perseverance, you won’t find a single, magical “Artificial Intelligence.” Instead, you’ll find a system of different, specialized software processes working in perfect synergy. Just as our brain manages sight, balance, and motor planning without us noticing, a rover’s brain does the same.

These processes answer three fundamental questions that any explorer (human or robotic) must ask:

- “Where am I, and what is around me?” (SLAM)

- “What’s the best way to get there?” (Pathfinding)

- “Watch out for that rock!” (Hazard Avoidance)

These three pillars are the anatomy of autonomous navigation. Let’s break them down.

3.1. SLAM: “Where Am I and What is Around Me?”

The acronym stands for: Simultaneous Localization and Mapping.

The Problem: A rover “wakes up” on Mars. There is no GPS. There is no satellite network telling it “You are here.” How does it know where it is? And how does it build a map of a place no one has ever seen before?

Imagine being blindfolded and left in a large, unknown cave with only a flashlight. You take off the blindfold. What do you do?

- You turn on the flashlight and look at the nearest rock formations (stalagmites, walls). You start to create a mental map.

- You take two steps forward.

- You look around again. You tell yourself, “Okay, that stalagmite that was in front of me is now to my left. Therefore, I must have moved two steps forward.” You are updating your position (localization) relative to the map you are building.

This is SLAM. It’s a “circular” problem (a classic chicken-and-egg problem): to know where you are, you need a map; but to make a map, you need to know where you are.

SLAM solves this by doing both simultaneously.

How It Works (in brief):

The rover uses its “senses” to map and localize:

- Eyes (Navcams): The stereo navigation cameras, like our two eyes, look at the landscape and calculate the distance of objects (rocks, dunes, crater rims) by creating a 3D map.

- Inner Ear (IMU): The Inertial Measurement Unit “feels” movement. It tells the rover, “You moved forward 50 cm and turned right 5 degrees.”

The rover runs a constant loop:

- Drive: It moves one meter using its IMU’s estimate.

- Look: It takes a stereo image with its Navcams.

- Think: It compares the new image with the map it already has. It identifies “landmarks” (features) it has seen before.

- Correct: The IMU might have said “I turned 5 degrees,” but by looking at the landmarks, the rover realizes, “Actually, a wheel slipped, and I only turned 4.8 degrees.” It corrects its position on the map and adds the new rocks it sees.

SLAM is the onboard cartographer, drawing the map as it goes.

3.2. Pathfinding: “What’s the Best Way to Get There?” 🗺️

Also known as: Path Planning.

The Problem: The rover now has a map (thanks to SLAM). On the map, it sees “Itself” (Point A) and a “science target” (Point B) that scientists on Earth have designated, perhaps 50 meters away. How does it get there?

Going in a straight line isn’t an option. The path could be blocked by a boulder, a slope that is too steep, or soft sand where it could get stuck.

The Pathfinding is the Rover-s “Google Maps”. This is the simplest and most effective comparison. When you ask Google Maps to take you to another city, it doesn’t just draw a straight line. The algorithm analyzes the map and calculates the optimal route based on various “costs”: distance, tolls, traffic, road closures, and even fuel consumption.

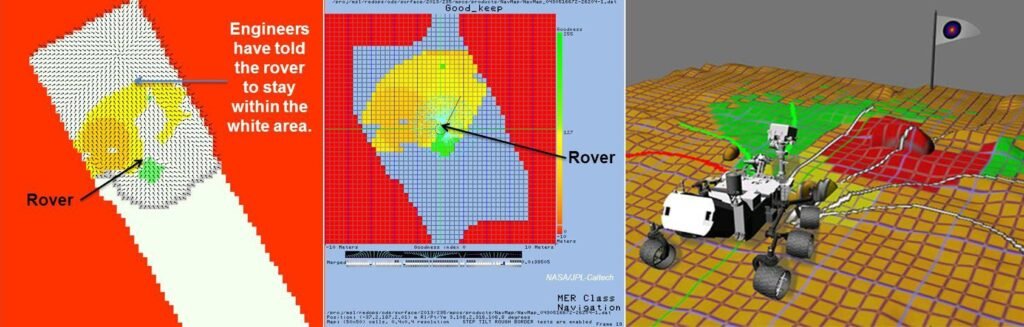

The rover does the same thing. Its software creates a “Cost Map” of the terrain.

- Flat, solid ground = Low Cost (Green)

- Sand or a slight slope = Medium Cost (Yellow)

- Sharp rocks, slopes > 30°, cliffs = Very High Cost / Forbidden (Red)

The Pathfinding algorithm (like the famous A* or D Lite*) “explores” thousands of virtual paths on this cost map and finds the one with the lowest total cost to get from Point A to Point B.

Important: There are two levels of Pathfinding:

- Global Planning (The Journey): This is the general plan to get to the waypoint 50 meters away, based on the big map (from SLAM and orbital photos). This is the “Google Maps” that tells you, “Take the I-95 highway.”

- Local Planning (The Maneuver): This is the plan for the next 2-3 meters. This is the “Google Maps” that tells you, “Move into the right lane now to avoid the stalled car.”

3.3. Hazard Avoidance: “Watch Out for That Rock!”

Also known as: Obstacle Avoidance.

The Problem: The Path Planner has charted a perfect course. But what if a rock was too small to be seen by the Navcams 10 meters away? Or what if a wheel slips and the rover veers 10 cm off course, straight toward an obstacle?

You need a short-range “reflex” system.

Imagine walking while surrounded by a virtual soap bubble that extends one meter in front of you. Your rule is: “Don’t let the bubble pop.” As you walk (following your Path Plan), you keep your eyes fixed on the edge of your bubble. If you see a sharp corner or a post about to “touch” the bubble, you stop immediately and take a step to the side, even if your original plan was to go straight.

How It Works (in brief):

The rover uses a different set of sensors: the Hazcams (Hazard Cameras).

- They are mounted low on the front and back of the rover.

- They are “wide-angle,” like a fly’s eyes. They aren’t for seeing far, but for seeing everything up close.

- They constantly create a 3D map of the terrain immediately in front of the wheels.

The Hazard Avoidance system receives the path from the Local Planner (e.g., “move forward 1 meter”) and checks it against the “bubble” created by the Hazcams.

- If the path is clear: OK, go.

- If the path is blocked: STOP! The Hazard Avoidance system issues a VETO on movement. “Stop the motors. The plan is not safe.” At this point, the rover’s brain recalculates a new Local Plan (e.g., “Okay, not straight. Turn left 10 degrees and try again.”).

Conclusion: A Team Working in Synergy

These three pillars don’t work in isolation. They are in a constant, high-speed feedback loop:

- SLAM (the cartographer) builds the map of the world.

- The Pathfinder (the navigator) uses that map to plot the best course.

- Hazard Avoidance (the pilot) keeps its eyes on the road and hands on the wheel, ready to brake and ask the navigator for a new route if the path is blocked.

All of this happens dozens of times a second. It is this ballet of software that transforms a 1000 kg “zombie” into an autonomous explorer. Now that we know what it does, in the next chapter, we’ll see how this technology evolved, from the first timid steps of Sojourner to the high-speed drives of Perseverance.

4. The Evolution: From Kitten to Cheetah 🐾

In the previous chapters, we saw why autonomy is necessary (latency) and what it’s made of (SLAM, Pathfinding, Hazard Avoidance). Now let’s see how these concepts evolved in the real world.

The progress of autonomous navigation isn’t just a story of faster computers; it’s a story of trust. It’s the journey that took NASA from micro-managing a “robot on a leash” to letting a multi-billion-dollar explorer “take the wheel” on another planet.

This evolution can be divided into four major eras, each with an analogy describing its level of intelligence.

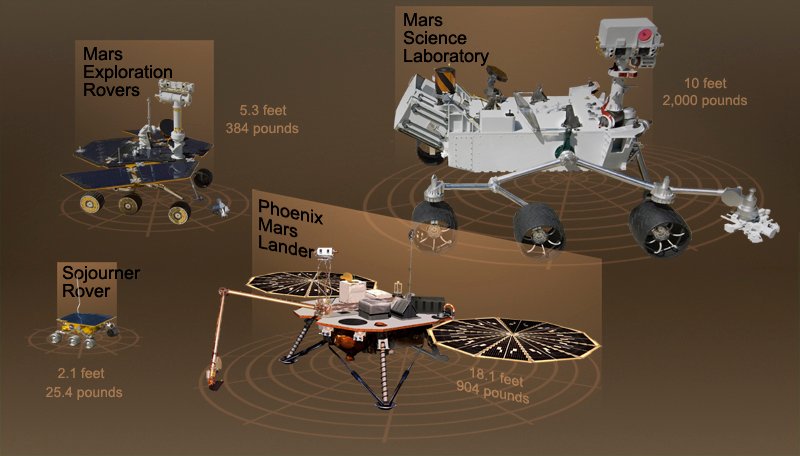

Era 1: The Baby (Sojourner, 1997)

- Mission: Mars Pathfinder

- Analysis: Sojourner, the first rover on Mars, was the size of a microwave oven. Its autonomy was almost non-existent; it was a reactive robot, not a proactive one.

- The Analogy: The Crawling Infant

Imagine an infant crawling. It doesn’t have a “plan” to cross the room. Its parents (JPL engineers) tell it “go forward.” It moves, but if it touches a toy with its hands (its sensors), it stops and waits for the parent to tell it what to do (e.g., “turn left and try again”). - How It Worked:

Sojourner had no stereo cameras for 3D mapping. It used a simpler system: five laser “whiskers” pointed forward.- An operator on Earth sent a command (e.g., “Move forward 50 cm”).

- The rover executed exactly that command.

- During the move, if one of its lasers detected a rock immediately in front of it, the safety system stopped everything.

- The rover would then wait, motionless, for hours, for the next command from Earth to solve the problem.

- The Result: It worked, but it was incredibly slow and dependent. There was no SLAM or Pathfinding. There was only basic “Hazard Avoidance.”

Era 2: The Teenagers (Spirit & Opportunity, 2004)

- Mission: Mars Exploration Rovers (MER)

- Analysis: These twin, golf-cart-sized rovers represented the first true leap in autonomy. They introduced the “AutoNav” (Autonomous Navigation) system.

- The Analogy: The New Driver

Imagine a teenager with a new driver’s license. You can tell them “go to the supermarket at the end of the street” (a waypoint). They won’t drive smoothly. They will drive for a few meters, come to a full stop at the stop sign, look carefully left and right, and only when certain it’s clear, proceed to the next stop sign. - How It Worked: “Stop-and-Think” Driving

For the first time, the rovers had stereo “eyes” (Navcams) to map in 3D. But their brains (RAD6000 computers) were too slow to drive and think at the same time.- Engineers gave them a target (e.g., “reach that rock 20 meters away”).

- The rover would drive forward about 1 meter.

- STOP.

- It would take a stereo picture with its Navcams.

- Its brain would analyze the image, build a 3D cost map, and plan the safe path for the next meter.

- Repeat the cycle.

- The Result: A stunning success (they were planned for 90 days; Opportunity lasted 15 years!), but their autonomous driving was a slow “ballet.” They spent more time thinking than moving.

Era 3: The Efficient Adult (Curiosity, 2012)

- Mission: Mars Science Laboratory (MSL)

- Analysis: Curiosity, the size of a small car, solved the “Stop-and-Think” problem. Its brain (a much more powerful RAD750 computer) was capable of doing two things at once.

- The Analogy: The Experienced Driver

This is an adult driver. They don’t stop at every intersection to look at the map. They drive with their eyes on the road (analyzing hazards) while simultaneously glancing at the GPS (planning the route). - How It Worked: Continuous Driving

This was the revolution. Curiosity’s brain “delegated” tasks:- A co-processor (FPGA) handled image acquisition from the Navcams and Hazcams, creating the 3D map in real-time.

- The main CPU used this constantly updated map to plan the path while the wheels were still turning.

- The Result: If Curiosity saw an obstacle, it didn’t stop. It simply steered gently around it, continuing to move. This doubled its cruising speed and efficiency, allowing it to cover far more ground.

Era 4: The Professional Athlete (Perseverance, 2021)

- Mission: Mars 2020

- Analysis: Perseverance (Curiosity’s twin, but with an upgraded brain) has perfected autonomous driving. It’s faster, smarter, and has better “eyes.”

- The Analogy: The Rally Driver

Perseverance isn’t just a driver; it’s a professional pilot. It doesn’t just “avoid” obstacles; it finds the fastest line through an obstacle field. It looks much farther down the road, and its brain processes information almost instantly. - How It Works: AutoNav 2.0

- Dedicated Brain: Perseverance has an entire separate “visual brain” (Vision Compute Element) dedicated exclusively to image analysis. This frees up the main computer (which is already an upgraded backup of Curiosity’s) to do high-level planning.

- Better Eyes: Its Navcams are higher-resolution, color, and have a wider field of view. It sees more, and it sees better.

- Speed of Thought: Thanks to this dedicated hardware, Perseverance calculates its 3D cost map in near-real-time. It can drive at its top autonomous speed (around 120 meters/hour) even over complex terrain.

- The Bonus (The Landing): Perseverance’s autonomy was on display before it even touched the ground. It used Terrain-Relative Navigation (TRN): during its descent, it took pictures of the ground below, matched them to an orbital map in its memory, and actively steered to avoid hazards and land in the chosen scientific “sweet spot.” It was the first true act of autonomous navigation on Mars.

Conclusion: From Obedience to Initiative

The journey from Sojourner to Perseverance is the shift from obedience to initiative.

- Sojourner said: “Tell me what to do. If there’s a problem, I’ll stop and wait for you.”

- Spirit said: “Give me a target. I’ll stop at every step to make sure I do it safely.”

- Curiosity said: “Give me a target. I’ll get there safely without stopping, unless I have to.”

- Perseverance says: “Give me a target. I’ll find the fastest way to get there.”

Now that we’ve seen the evolution on Mars, the next chapter will tackle a completely different challenge: why the Moon, so close, is a navigator’s nightmare.

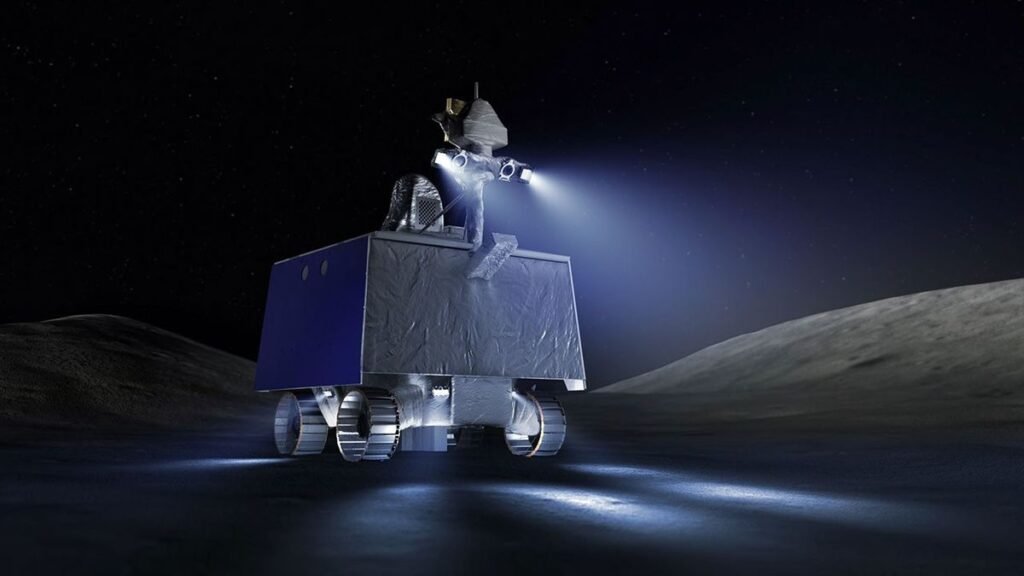

5. The Lunar Challenge: The Backlighting Nightmare

Our journey has taken us from Mars to the Moon, but one shouldn’t make the mistake of thinking the Moon is just “Mars, but easier.” Although it’s closer (less latency), for a robot, navigating on the Moon is, in some ways, a worse technological nightmare.

The problems aren’t distance; they are light and dust.

1. The Light Problem: Extreme Contrast

On Mars, there is a thin atmosphere that, like on Earth, “scatters” sunlight. This softens shadows and slightly illuminates areas not in direct sun.

On the Moon, there is no atmosphere. This creates a high-contrast hellscape that deceives sensors:

- Pitch-Black Shadows: A shadow isn’t just dark; it’s absolute black. A camera sensor sees only black pixels, void of data. A deep crater and a flat shadow look identical: a black hole of information.

- Blinding Light: Areas in direct sunlight are so bright they “burn out” the sensors (saturation). Rocks and details disappear into a white glare.

For a rover that relies on stereo vision (which needs to see contrast and features to calculate distances), this is a disaster. It’s like trying to tell a puddle from a chasm in a world painted in only absolute black and white.

2. The Dust Problem: Regolith

Lunar dust, or regolith, isn’t like house dust. It’s the result of billions of years of micrometeorite impacts. It’s as fine as flour, as abrasive as ground glass, and, due to solar radiation, electrostatically charged.

It sticks to everything: solar panels, gears, and, most critically, camera lenses and LiDAR sensors, effectively blinding the rover.

The Lunar Solution: Future lunar rovers (like NASA’s VIPER) cannot rely on passive cameras as they do on Mars. They will heavily use active sensors like LiDAR (which shoots laser pulses to map in the dark) and will be equipped with powerful LED headlights to “paint” the scene and artificially light those deadly shadows.

6. Conclusion: The Future is Initiative

We started with a cosmic problem: the Tyranny of Latency. We saw that the only solution to explore space is to build a brain.

We disassembled that brain into its three pillars: SLAM (the cartographer), Pathfinding (the navigator), and Hazard Avoidance (the pilot). We followed their evolution from a frightened “infant” (Sojourner) to a “rally driver” (Perseverance), and we learned why the nearby Moon presents even greater challenges.

But autonomous driving is just the beginning.

Until now, rovers have been “smart” at executing our commands: “Go to that rock.” The next step is initiative. The future of exploration isn’t a robot that executes, but a robot that thinks.

The next generation of rovers will use AI to make autonomous scientific decisions. Their thought process won’t be “How do I avoid that rock?” but rather:

“My analysis of this hill shows an interesting geological anomaly 500 meters to the west. I am deviating from the original plan. I have decided to investigate.”

This is the true goal: to create a robotic field geologist, a pioneer that doesn’t just follow the map, but decides where to draw it.

This article was your map of the territory. It’s the foundation upon which we will build everything else. In the coming weeks and months, we will put every single piece of this puzzle under the microscope, from the A* algorithms that drive Pathfinding to the “radiation-hardened” hardware that survives in space.

The journey has just begun.

Lascia un commento