I. Introduction: The Space “Video Game” Paradox

Imagine you’re in the middle of a high-stakes video game. You push the joystick, your avatar sprints. You see an obstacle, you swerve instantly. Total control, immediate feedback. Now, imagine piloting a multi-billion dollar rover on Mars. Why can’t we just “drive” it with a joystick? If we see a cliff, why can’t we just hit the “brakes”? The answer is brutal and unavoidable: our real enemy is physics. It’s called latency, the 20-Minute Lag

Latency isn’t just a simple, trivial delay; it’s a abyss of time. A chasm that could cost us millions and millions of dollars and sacrifices. This fundamental delay has forced us to redefine the very concept of control, shifting from real-time piloting to teaching robots how to think for themselves and navigate new worlds.

This article will primarily compare the communication lag between Earth and other planets, analyzing how communication solutions have evolved to meet these unique challenges. We will understand how communication systems evolved from “shouts in the void” to autonomy, and we will conclude with an analysis of what the future may hold.

II. The Fundamental Comparison: Moon vs. Mars

To grasp the Martian challenge, we must first take a trip to our next-door neighbor: the Moon. The difference between “near” and “far” in space is not a matter of kilometers, but of seconds.

The Moon: The 2.5-Second Echo

The Moon is, in cosmic terms, just around the corner. At about 384,400 km (238,855 miles) away, light takes about 2.5 seconds for a round-trip journey.

This is the famous delay we all heard during the Apollo missions. Remember the conversations between Houston and Neil Armstrong? “One small step for man…” and then that characteristic pause before Houston’s reply. It wasn’t for dramatic effect; it was physics. It was a conversation, albeit slightly out of sync.

With 2.5 seconds, you can almost pilot in real-time. The Soviets managed it in the 1970s with their Lunokhod rover. A team of “pilots” on Earth drove it while watching a video feed, but they had to anticipate every move. Between the signal lag and human reaction time, the effective delay was 5-10 seconds. It was nerve-wracking, difficult, but doable.

We must add, however, that the problem with the Lunokhod mission wasn’t just the lag, but also the extremely low bandwidth. Modern rovers send smooth videos. Lunokhod did not. Its stereoscopic cameras (two “eyes”) didn’t send a video feed, but a single static image at a very low scan rate. Depending on the mode, it could take from 3 to 20 seconds to transmit a single frame.

This changed everything. The “pilot” wasn’t driving while watching a delayed film; they were looking at a slide. For this reason, they used a “Stop-and-Go” method.

We will, however, return to this point later in the article.

Mars: The 40-Minute Abyss

Now, take that delay and forget it. Mars is playing in a completely different league.

The Red Planet isn’t a stationary target; its distance from Earth varies wildly, from 55 million to over 400 million kilometers (34 million to 250 million miles). This means the round-trip “lag” isn’t fixed: it ranges from 6 to 44 minutes. The “20-Minute Lag” in our title is just a convenient average.

What does this mean in practice?

Imagine this nightmare scenario. Your multi-billion dollar rover is advancing, and its camera spots a cliff. That image takes 6 minutes (at best) to cross space and arrive on your screen in Houston. You see the danger and yell “BRAKE!” Your command, traveling at the speed of light, takes another 6 minutes to get back to Mars.

The result: 12 minutes have passed. In that time, the rover didn’t stop and wait for instructions. It continued driving straight into the void for 12 minutes.

Here is the brutal conclusion: “driving” a rover on Mars isn’t just difficult. It is physically and absolutely impossible!

III. The Evolution of Communication Solutions

This chapter presents a quick roadmap of how communication systems have evolved across different missions.

A. The First Solutions: “Shouts in the Void” (’60s – ’90s)

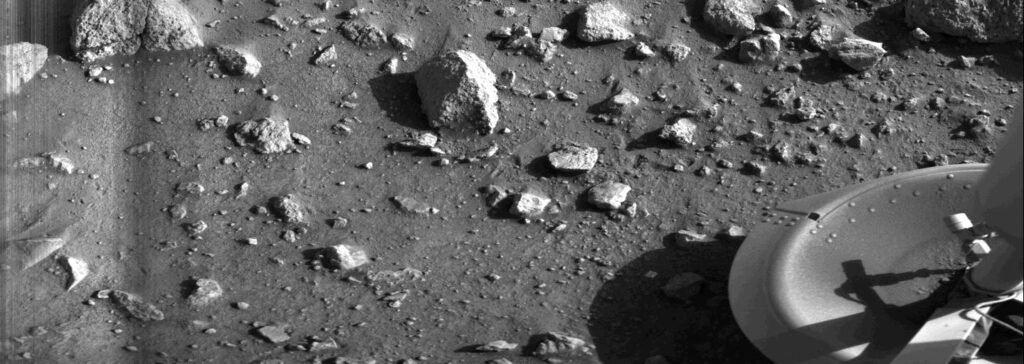

In the early eras of exploration, there was only one strategy: Direct-to-Earth (DTE) communication. Iconic missions like Mariner and Viking essentially “shouted in the void,” hoping the massive antennas of the Deep Space Network on Earth could pick up their faint signal.

This approach had brutal limitations:

- Low Data Rate: The bandwidth was almost non-existent, measured in bits per second. The first historic images from the surface of Mars weren’t a download, but a slow trickle of data that took hours, sometimes an entire day, to compose a single grainy photo.

- The Line-of-Sight Problem: Communication only worked when the probe’s antenna could physically “see” Earth.

Even the first rover, the pioneer Sojourner (1997), couldn’t talk directly to Earth. It was entirely dependent on its lander, Pathfinder, which acted as its base station. Control was an exercise in patience and faith: engineers would send a short sequence of “Store-and-Execute” commands, like “move forward 2 meters, turn left, measure the rock.” Then, they would wait until the next day to see if the rover had executed the order or gotten stuck.

B. The Modern Era: The Birth of the Martian “Network” (2000s – Today)

The real revolution arrived when we stopped “shouting” and started building a network.

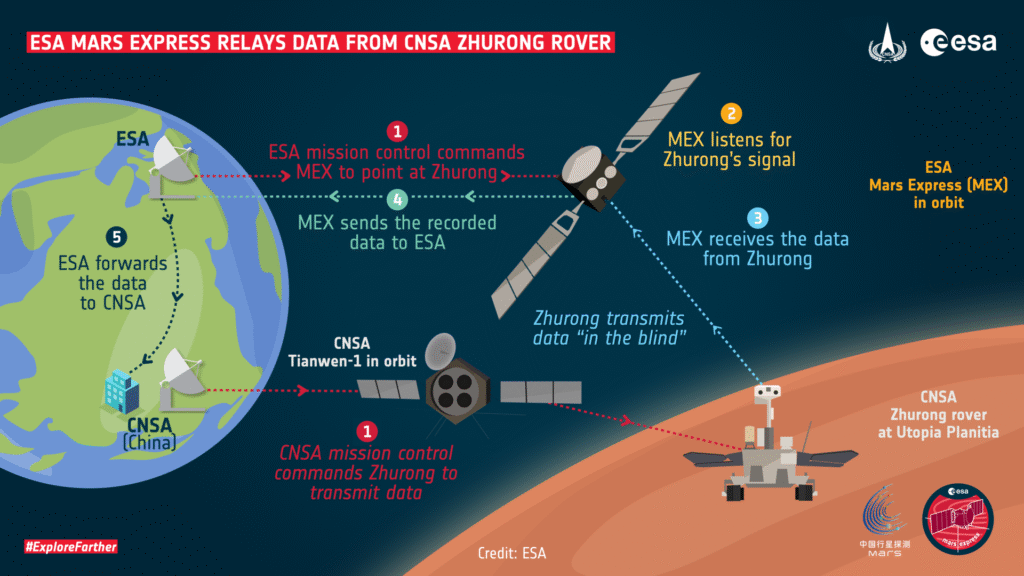

The Revolution: Orbiters as Relays The key solution was to stop relying on direct communication. Modern rovers—from Spirit and Opportunity to Curiosity and Perseverance—use a two-step strategy: they make a high-speed “local call” to the orbiters speeding above them (like the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, Odyssey, or MAVEN).

This system changed everything for two reasons:

- Greater Bandwidth: The orbiter is close to the rover (a strong signal) and has a huge antenna and more power to relay data to Earth. It was like upgrading from a 56k modem to fiber optics. Suddenly, we could receive HD video and a volume of scientific data that was previously unthinkable.

- It Solves the Line-of-Sight Problem: The orbiter acts as a celestial “courier.” The rover can send its data to the orbiter even if Earth is hidden behind the planet. The orbiter stores the data (“store-and-forward”) and waits until it has a clear view of Earth to send the entire package at high speed.

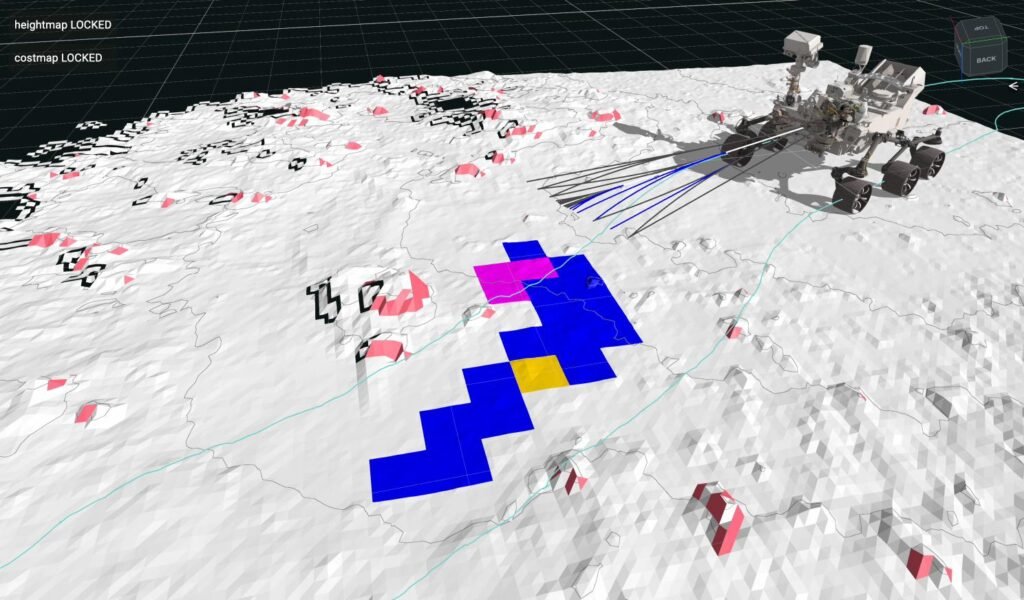

The Solution to the Lag: Autonomy (AutoNav) But the orbiter network solves the data volume problem, not the delay problem. To solve the “20-Minute Lag,” the only solution was autonomy. Since we can’t drive, the rover must learn to drive itself.

This evolution was gradual:

- Yesterday (Spirit and Opportunity): Theirs was a cautious autonomy. Engineers would designate an endpoint. The rovers would advance slowly, stop every meter, take photos, and analyze the terrain in front of them to decide the next move. It was a slow, “stop-and-think” process.

- Today (Perseverance): Thanks to much more powerful onboard computers, Perseverance uses a system called AutoNav. Engineers can say, “Go toward that hill over there.” The rover moves at a constant speed, using its navigation cameras to map the terrain and identify and avoid obstacles in real-time, without stopping. It’s no longer a simple command executor; it’s a robotic co-pilot making immediate decisions for its own safety.

IV. Additional Problems and Future Solutions

If the 20-minute delay were the only obstacle, mission planning would be (relatively) simple. But the interplanetary environment adds complications that require even more sophisticated engineering solutions.

A. Other Communication Challenges

The lag is constant, but these challenges are periodic and just as dangerous.

- Solar Conjunction: Every 26 months or so, Earth and Mars are on opposite sides of the Sun. This isn’t just a physical “block”; the Sun emits an enormous amount of superheated plasma that corrupts and annihilates any radio signal trying to pass through it. For the two-week duration of this event, all communication is severed. Mission teams cannot send commands or receive data. The rovers are forced into an operational “blackout,” stop moving, and only execute pre-loaded basic maintenance commands, waiting silently for Earth to reappear on the other side.

- Dust Storms: Unlike what you see in the movies, Martian dust storms are not a threat to radio communications. The fine dust, although it can obscure the entire planet, has a negligible impact on radio waves in the X or Ka bands. The real danger of global storms is energy-related: by blocking the Sun, they starved the solar-powered rovers, as fatally happened to Opportunity. For nuclear-powered rovers like Curiosity and Perseverance, however, a dust storm is just a weather nuisance, not a communication block.

B. The Future: More Data, Same Lag

Looking ahead, it is imperative to accept one truth: you can’t change physics. The speed of light is an absolute limit. The engineering goal, therefore, is not to make communication more instant, but to make it richer and more reliable.

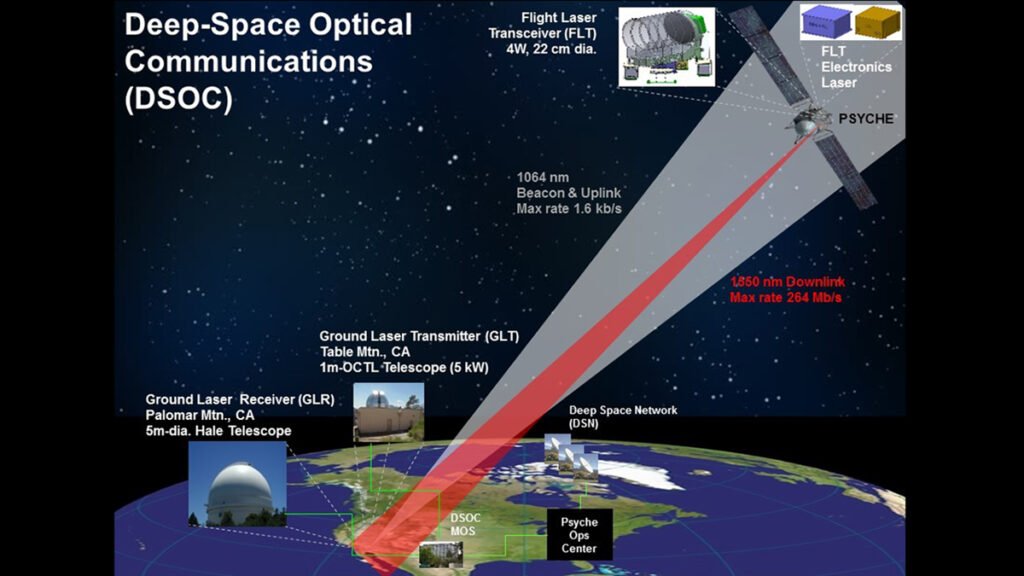

- Solution 1: Laser (Optical) Communications The next revolution will be the shift from radio waves to lasers. NASA is already testing this technology with missions like LCRD (Laser Communications Relay Demonstration) and the experiment aboard the Psyche probe. Instead of radio waves, an infrared laser beam is used, which is much more concentrated. The advantage is an exponential increase in bandwidth, potentially 10 to 100 times greater. This means being able to download entire high-resolution 3D maps or 4K video from Mars in minutes instead of days. But the fundamental paradox remains: we will receive a breathtaking 4K video, but we will always receive it 20 minutes late.

- Solution 2: The Interplanetary Internet The other frontier is infrastructural. It requires strengthening our Deep Space Network (DSN)—the three giant antenna stations on Earth that listen to the cosmos—to handle more data traffic. But above all, it requires the creation of a dedicated network of permanent relay satellites around Mars. Imagine a Martian “GPS” or “Starlink”: a constellation providing 24/7 high-speed coverage, eliminating the need to wait for a science orbiter to pass overhead. In parallel, the future Lunar Gateway for the Artemis program will act as a crucial communication hub, a “server” in lunar orbit, vital for supporting human and robotic missions, especially on the far side of the Moon, which is otherwise unreachable from Earth.

Research into optical (laser) communications is a rapidly expanding field, as it is considered the primary solution to the bandwidth “bottleneck” of radio frequency (RF) communications.

V. Conclusion: From “Pilots” to “Supervisors”

We started with a simple paradox: why can’t we “drive” a multi-billion dollar rover on Mars like a video game avatar? Now the answer is clear and inescapable. We can’t use joysticks to command our robots not due to a lack of technology, but due to an excess of distance. The “20-Minute Lag” isn’t a bug to be fixed or a connection problem; it’s a fundamental law of the universe.

It was precisely this insurmountable physical barrier that forced us to make the true evolutionary leap. The challenge of the lag forced us to stop thinking like drone pilots, desperately clinging to a real-time control we could never have, and to start thinking like artificial intelligence programmers. It transformed us from “pilots” to “supervisors” of increasingly autonomous robots.

The evolution of space communication, therefore, is not just about data transmission speed. Sure, future laser systems will solve the bandwidth “bottleneck,” allowing us to receive 4K video, but that video will always arrive 20 minutes late. The real achievement is not data speed, but the development of intelligent autonomy that allows us to explore even when we cannot be “present” in real-time.

But the challenge doesn’t end here. If lag is the problem of control and bandwidth is the problem of data, the next frontier will be energy. From my perspective, the next laser revolution will not only be about sending photons to inform, but also about sending photons to power. Innovative companies, like SunCubes, are already designing systems to recharge satellites and rovers directly from Earth via laser power beaming.

Only by mastering this triad, autonomy to defeat the lag, optical communications for the data, and laser energy for sustainability, can we finally transform exploration from a series of cautious “visits” into a continuous robotic presence on distant worlds.

The challenge of lag has been won by autonomy. The next one, energy, has just begun. Subscribe to continue exploring the frontiers of technology with me.

Lascia un commento