Navigating celestial bodies autonomously presents a unique hurdle that we don’t face on Earth: the complete lack of Global Positioning System (GPS). In this context, a rover’s ability to understand its own location becomes a complex mathematical problem. In advanced robotics, the standard answer to this problem is SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping). In this article, we’ll break down the core principles of SLAM, examine how it’s critical for current Mars missions, and look at the immense computational strain it puts on space-grade hardware.

Introduction: The Problem of Navigation in “GPS-Denied” Environments

On Earth, localization is trivial thanks to satellite constellations like GPS or Galileo. On Mars, Titan, or Europa, a rover operates in a strictly “GPS-denied” environment.

In the absence of external references, a robot could theoretically rely on Dead Reckoning, using internal data from wheel odometry (counting rotations) and IMUs (Inertial Measurement Units – accelerometers and gyroscopes). However, this method is subject to drift: small measurement errors accumulate rapidly over time. An initial orientation error of just a few degrees can translate into a deviation of hundreds of meters after a kilometer of travel. This is unacceptable for precision scientific missions. The SLAM algorithm was created to correct this drift by observing the surrounding environment.

The SLAM Paradox: Mapping While Navigating

The central problem that SLAM solves is often described as a chicken-and-egg paradox:

- To localize precisely, the rover needs a map of the environment.

- To build a map of the environment, the rover needs to know its precise location.

The SLAM algorithm addresses both needs simultaneously through an iterative stochastic (probabilistic) process. It uses advanced mathematical filters, such as the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) or Particle Filters, to manage uncertainty.

The simplified operational cycle is:

- Predict: The rover estimates its new position based on its movement commands (e.g., “I moved forward 1 meter”).

- Measure: Sensors observe “landmarks” (reference points) in the environment.

- Update: The algorithm compares the predicted position of landmarks with the observed one and corrects both its own position estimate and the map itself.

Visual SLAM (vSLAM): The “Eyes” of Martian Rovers

While autonomous vehicles on Earth often use LiDAR (laser scanners) for SLAM, in space, weight and power consumption are severe constraints. For this reason, NASA and other agencies have heavily focused on Visual SLAM (vSLAM).

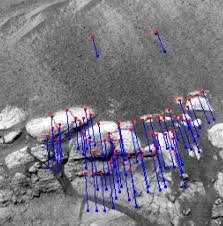

Using stereoscopic cameras (like Perseverance’s Navcams), the rover doesn’t “see” rocks in the human sense but extracts features: high-contrast points, sharp edges, or unique textures. The algorithm tracks these points between successive frames.

A crucial concept in vSLAM is Loop Closure. When the rover recognizes a landmark configuration it has seen in the past (closing the loop), it can use this information to “relax” the map, retroactively correcting all drift errors accumulated since it last visited that point.

Technical Deep Dive: From EKF to Graph-SLAM

To handle mathematical complexity, early SLAM implementations often relied on the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF). The EKF is efficient because it is a recursive filter: it estimates the current state and then “forgets” past poses (marginalization). However, this approach “bakes in” (irreversibly incorporates) linearization errors, leading to inconsistent maps over long distances.

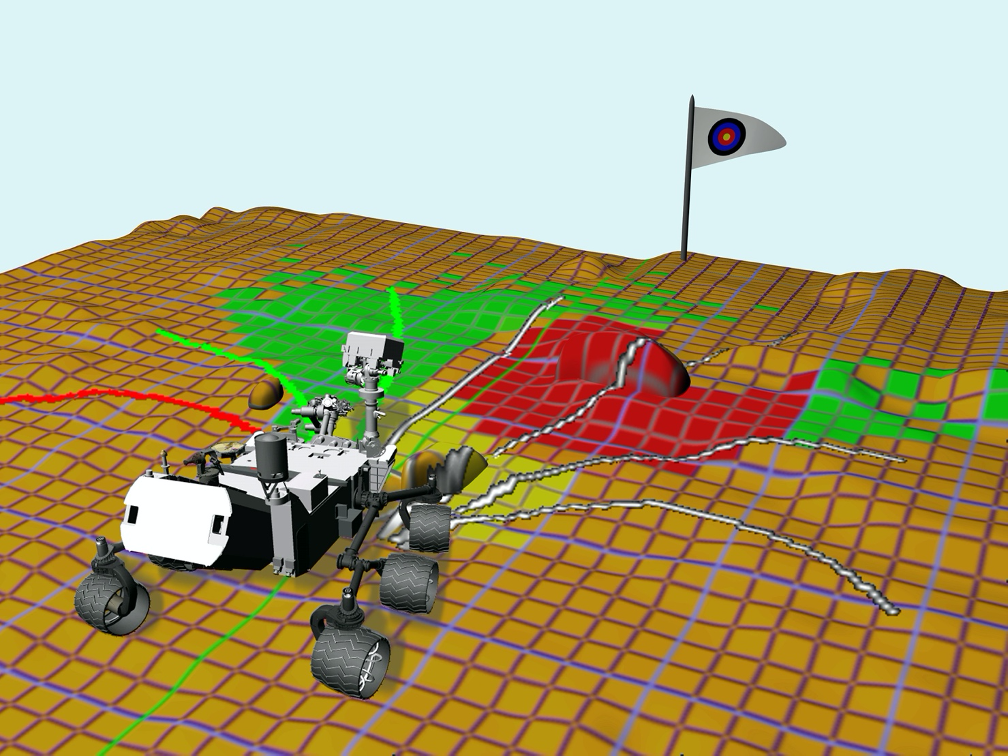

Modern space robotics has shifted towards Graph-SLAM (or approaches based on Factor Graphs). In this paradigm, the rover doesn’t just track its current position but keeps the entire trajectory in memory as a graph:

- Nodes: Represent the rover’s historical poses and landmark positions.

- Edges: Represent spatial constraints derived from sensor measurements (e.g., “I was 2 meters from landmark X”).

When a Loop Closure occurs, the system doesn’t just make a small correction but performs a global non-linear least squares optimization (often using solvers like Levenberg-Marquardt or Gauss-Newton) on the entire graph. This process elastically “stretches” and relaxes the rover’s entire navigation history, distributing accumulated error over thousands of past poses and ensuring topological map consistency that would otherwise be impossible.

The Algorithmic Nightmare: “Perceptual Aliasing” on Mars

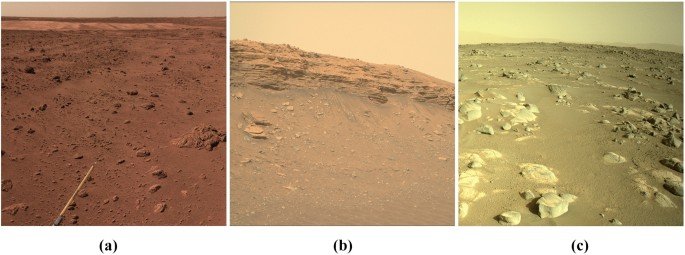

A critical danger for SLAM in extraterrestrial environments is high terrain self-similarity: a dune field or a basaltic rock plain can appear nearly identical in different locations. This phenomenon leads to Perceptual Aliasing, where the algorithm erroneously associates current sensory input with a different, but visually identical, past location.

If unmanaged, this generates a “False Positive Loop Closure”: the rover “believes” it has returned to a previous point when it hasn’t. Inserting this incorrect constraint into the Factor Graph can lead to catastrophic map failure, causing it to collapse on itself or become irreparably distorted. To combat this, modern SLAM back-ends don’t blindly trust every loop closure. They implement robust techniques like Switchable Constraints or use robust cost functions (e.g., Huber loss or Tukey biweight) during optimization, allowing the mathematical system to “reject” and deactivate constraints that are statistically inconsistent with the rest of the trajectory, saving the mission from a robotic “hallucination.”

Computational Challenges: Running SLAM on Dated Processors

Running SLAM in real-time requires significant computing power, a scarce resource in space. “Rad-hard” (radiation-hardened) processors, like the RAD750 used on Curiosity and Perseverance, are technologically decades behind terrestrial consumer CPUs to ensure reliability.

- Curiosity’s Bottleneck: Due to these limitations, the Curiosity rover often had to stop after short drives to take photos, process them on the ground, or wait for the onboard computer to complete navigation calculations.

- Perseverance’s Solution: For the Mars 2020 mission, JPL introduced a dedicated coprocessor based on FPGA (Field-Programmable Gate Array) for computer vision. This allows image processing and vSLAM to run in parallel while the rover moves, enabling much smoother and faster “thinking-while-driving” navigation.

The Future is Hybrid Sensor Fusion

Although vSLAM is the current gold standard for Mars, my analysis is that for future exploration missions—especially those in extreme environments like Martian lava tubes or Titan’s methane seas—vision alone will not suffice.

The future of space SLAM lies in advanced Hybrid Sensor Fusion. I foresee systems that do not rely on a single primary sensor but fuse different technologies in real-time. The first is certainly vSLAM for general navigation in illuminated environments, followed by solid-state LiDAR (lighter and more efficient than current mechanical models) for precise mapping in darkness or low-texture conditions. Finally, atomic-grade inertial navigation to reduce base drift before SLAM even needs to correct it.

Furthermore, the next qualitative leap won’t just be geometric (“there is an obstacle there”), but semantic (“that obstacle is soft sand I might get stuck in”). Integrating deep neural networks directly into the SLAM loop will allow rovers not only to know where they are but to understand what surrounds them.

Conclusion

The SLAM algorithm is much more than just a mapping tool; it is the fundamental prerequisite for robotic autonomy in deep space. Without the ability to localize precisely in real-time, no advanced research or sample return mission would be possible.

Lascia un commento