From the busy streets of San Francisco to the test tracks of Europe, the buzz around autonomous driving is deafening. Companies like Luminar pushed the boundaries of this revolution, equipping vehicles with sleek, high-tech sensors like the “Iris” that promise to map our highways with millimeter precision, spotting hazards through fog and rain. Seeing this incredible technology in action, it begs a logical question: if we have such advanced, relatively affordable “eyes” right here on Earth, why doesn’t NASA just strap one of these sensors onto the next Mars Rover and call it a day? It would save millions of dollars and years of development. The answer reveals one of the harshest truths of space exploration: the tyranny of latency. As we explored in our analysis of the [20-Minute Lag], we cannot joystick a rover in real-time; the vehicle must rely on its own senses to survive. While the basic physics of light detection remains the same, the engineering reality creates a massive, unforgiving divide in the battle of Automotive vs. Space LiDAR. It turns out that a sensor designed to survive rush hour traffic is woefully unprepared for the radioactive freeze of the Red Planet.

The Earthly Contender: How Automotive LiDAR Works

To understand why a sensor might fail on Mars, we first need to appreciate the genius of how it works here on Earth. At its core, LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) is essentially echolocation for robots, similar to how a bat navigates a dark cave, but using light instead of sound.

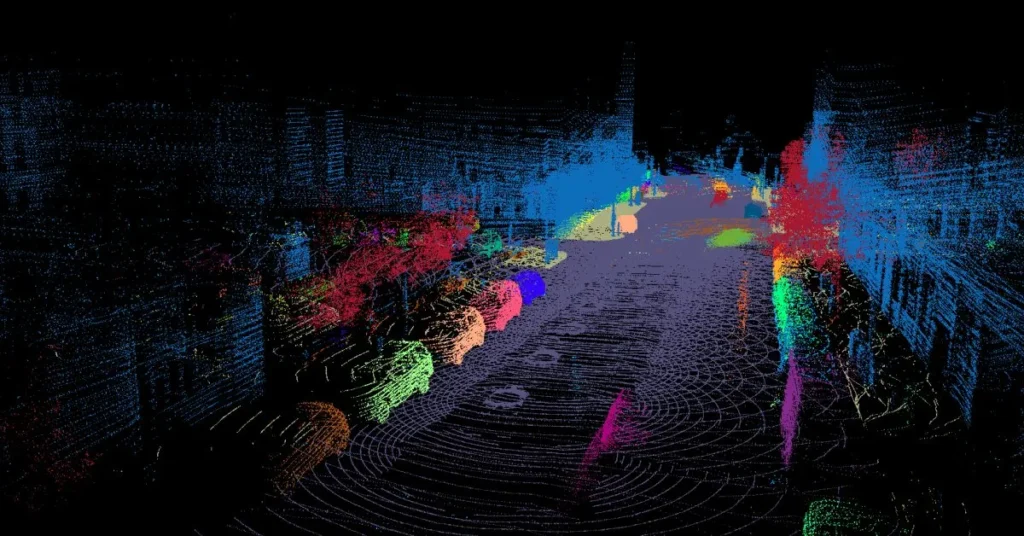

The concept relies on a principle called Time-of-Flight (ToF). The sensor fires a laser pulse at the speed of light, the pulse bounces off an object (like a pedestrian or another car), and returns to the sensor. By measuring exactly how many nanoseconds this round-trip takes, the computer calculates the precise distance. When you repeat this process millions of times per second, spinning the laser 360 degrees, you don’t just get a distance measurement; you get a 3D Point Cloud. Imagine a digital painting made entirely of millions of tiny floating dots, creating a perfect, real-time ghost replica of the world around the car.

This is where companies like Luminar pushed the envelope. Their sensors utilized a specific laser wavelength—1550 nanometers. Unlike the cheaper sensors found on robot vacuums, this higher wavelength allowed them to pump more power into the laser without damaging human eyes. The result? A sensor that could “punch” through atmospheric interference like fog or rain and detect obstacles hundreds of meters away on a highway.

However, as impressive as this technology is, we have to admit one thing: automotive sensors are pampered.

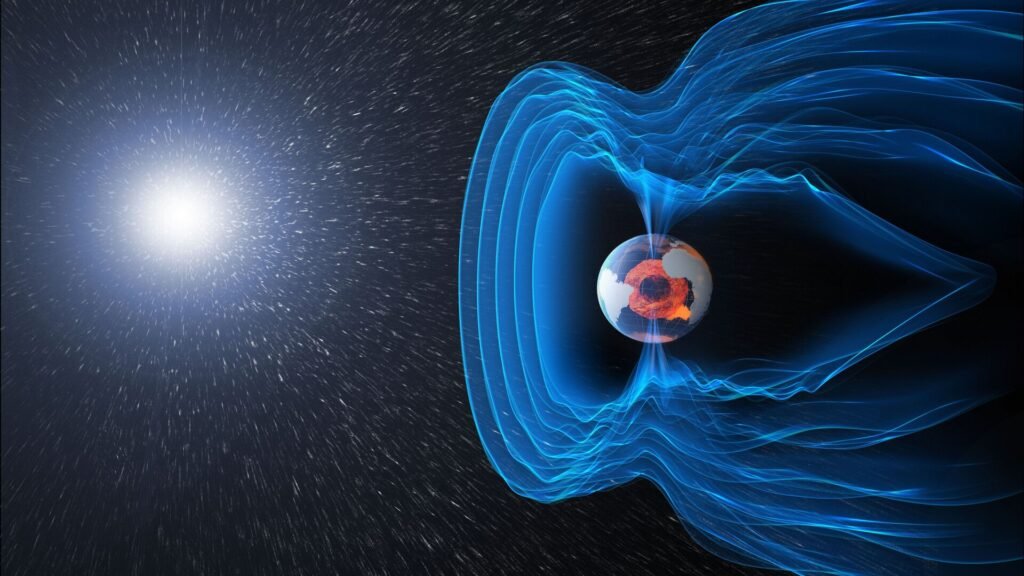

Operating on Earth is like living in a luxury resort for electronics. Our planet provides a thick atmosphere that acts as a thermal blanket, keeping temperatures relatively stable. More importantly, Earth’s magnetic field acts as a giant invisible shield, blocking the vast majority of deadly cosmic radiation. A sensor on a self-driving car in California might complain about a hot summer day or a bumpy road, but it has never had to face the true, raw hostility of the universe. It takes these “creature comforts” for granted—luxuries that simply do not exist on the Red Planet.

The Martian Reality: Why Earth Tech Fails

Once a sensor leaves Earth’s protective embrace, the rules of the game change entirely. The environment of Mars is not just difficult; it is actively trying to destroy electronics. If you took a standard automotive LiDAR off the assembly line and dropped it onto the Martian surface, it wouldn’t just stop working—it would likely suffer catastrophic structural and digital failure. Here is why.

1. The Radiation Trap (The “Invisible Bullet”)

On Earth, the atmosphere blocks most high-energy particles. In space, however, electronics are constantly bombarded by cosmic rays and solar flares. For engineers, this threat comes in two forms: TID (Total Ionizing Dose), which is the slow accumulation of radiation damage over time (like rust eating away at a car), and SEEs (Single Event Effects).

Think of an SEE as a sniper shot. A single subatomic particle can strike a microchip at near light-speed. If it hits the wrong transistor, it can “flip a bit”—changing a 0 to a 1 in the code.

- The Automotive Approach: Commercial chips (known as COTS – Commercial Off-The-Shelf) are like unshielded civilians walking through a crossfire. They rely on the safety of Earth. One hit, and the LiDAR might reboot or freeze entirely.

- The Space Approach: Space-grade chips are built like tanks. As detailed in the [Evolution of Rover AI], processors like the RAD750 are engineered specifically to withstand these cosmic bombardments, unlike fragile consumer electronics.. They use special materials and redundant circuits so that if a “bit flip” occurs, the system corrects itself instantly without crashing the rover.

2. The Thermal Rollercoaster

Temperature on Earth is relatively gentle. On Mars, the temperature swings are violent. A rover might experience a balmy +20°C at noon, only to plunge to -120°C at night. This cycle happens every single Martian day (Sol).

Materials expand when hot and shrink when cold. When you repeat this expansion and contraction cycle thousands of times, standard automotive electronics face a physical limit. The metal solder joints that hold the chips to the circuit board eventually succumb to thermal fatigue. In a standard sensor, the soldering would crack and shatter, literally disconnecting the brain from the body.

3. The Vacuum Problem (Outgassing)

There is a subtle enemy in space design that automotive engineers rarely worry about: Outgassing. Cars are full of adhesives, thermal pastes, and plastics. On Earth, these materials are stable. But in the near-vacuum of Mars’ atmosphere, volatile chemicals trapped inside these materials begin to “boil off” as gas.

If a standard Luminar sensor were placed in a vacuum, the glues holding the lens in place might release a fine mist of gas. Since there is no wind to blow it away, this gas would settle on the nearest cold surface—usually the sensor’s own glass lens. The result? The LiDAR would slowly fog itself up from the inside, blinding itself permanently with its own construction materials.

The SWaP Factor (Size, Weight, and Power)

Even if we could magically shield the sensor from radiation and temperature, we hit the ultimate bottleneck of space exploration: SWaP. This acronym stands for Size, Weight, and Power.

In the automotive world, power is cheap. An electric vehicle like a Tesla carries a massive battery pack capable of delivering kilowatts of energy effortlessly. If a LiDAR sensor needs 30 or 40 Watts to run its lasers and cooling fans, the car’s battery doesn’t even blink.

On Mars, power is the most precious currency. A massive rover like Perseverance doesn’t have a giant battery; it runs on a nuclear generator called an MMRTG (Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator). Despite its scary name and high cost, it produces only about 110 Watts of electricity.

Think about that. The entire rover—its driving motors, its computer brain, its drilling arm, and its communication radio—must all run on less power than a single bright lightbulb.

In this energy-starved environment, an automotive LiDAR is simply too greedy. Space engineers have to design sensors that are ultra-efficient, often sacrificing resolution or speed just to save a few precious Watts of power. A sensor that drains 25% of the rover’s total energy supply simply isn’t an option, no matter how good its map is.

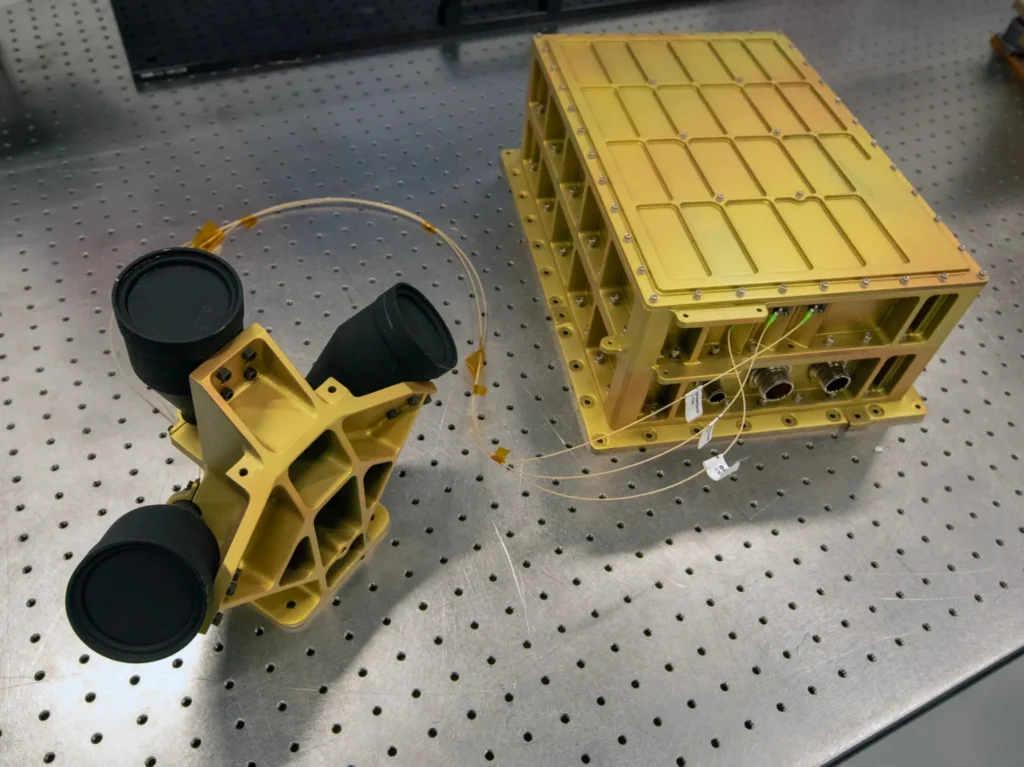

Case Study: Luminar Iris vs. NASA’s NDL

To truly appreciate the engineering divide, we need to stop talking in abstract terms and look at the raw numbers. Let’s pit the pride of the automotive industry—the Luminar Iris—against NASA’s heavy hitter, the Navigation Doppler Lidar (NDL).

While both devices use laser light to measure distance, their design philosophies are diametrically opposed. One is built to mass-produce data for highways; the other is built to guarantee survival during the most dangerous seven minutes in spaceflight.

| Feature | Luminar Iris (Automotive) | NASA NDL (Space Grade) |

| Primary Mission | Detecting pedestrians & cars on highways. | Landing a spacecraft safely on Mars (EDL). |

| Measurement Type | 3D Point Cloud (Shape & Distance). | Doppler Velocity + Range (Speed & Distance). |

| Maximum Range | ~500 meters (for highly reflective objects). | ~6,000 meters (to find the ground from orbit). |

| Power Consumption | ~25 Watts (Battery friendly). | ~80 Watts (Huge drain, used only for minutes). |

| Precision | Centimeter-level accuracy. | Millimeter-level velocity precision (<0.2 cm/s). |

| Mass | Compact & Lightweight (< 2kg). | Heavy (~14kg total system weight). |

| Cost | ~$1,000 (Mass production target). | Millions (Custom R&D and fabrication). |

The Verdict: The Luminar Iris is a marvel of efficiency, creating beautiful 3D maps using very little energy. However, it is “blind” to velocity—it can tell you where an object is, but not exactly how fast it is moving towards you in real-time. The NASA NDL, on the other hand, is a beast. It is heavy, power-hungry, and insanely expensive, but it offers something money can’t buy on Earth: it can calculate the rover’s speed towards the ground with a precision of a few millimeters per second. When you are falling towards Mars at supersonic speeds, that data is the difference between a soft landing and a new crater.

The Exception: When “Cheap” Parts Go to Mars (Ingenuity)

Now that we have established that consumer hardware is unfit for Mars, it is time for the plot twist. If you look closely at Ingenuity—the tiny helicopter that hitched a ride on the belly of the Perseverance rover—you will find a shocking component.

To measure its altitude, Ingenuity did not use a million-dollar NASA sensor. It used a Garmin Lidar-Lite v3.

Yes, you read that right. The exact same $129 sensor that hobbyists buy on Amazon to put on their DIY Arduino robots was flying on Mars.

How is this possible?

This seems to contradict everything we just analyzed about radiation and thermal failure. But the success of the Garmin sensor on Ingenuity comes down to a calculated engineering gamble known as Risk Class.

- Mission Critical vs. Tech Demo: The Perseverance rover is a “Flagship Class” mission. It must survive for years; if it fails, the mission is over. Ingenuity, however, was a “Technology Demonstration.” It only had to survive for 30 days and 5 flights. If it crashed, it was acceptable.

- Short Exposure: The helicopter spent most of its life asleep, tucked safely under the rover or kept warm by heaters. It only flew for 90-second bursts. This minimized the sensor’s exposure to the brutal environment.

- The SWaP Necessity: Ingenuity weighed less than 1.8 kg (4 lbs).1 It simply could not carry a heavy, shielded NASA Lidar. The engineers had no choice but to use the Garmin unit, which weighs a mere 22 grams and consumes almost no power (~0.6 Watts).

The Lesson: The Garmin Lidar-Lite v3 worked brilliantly, but it was a sprinter, not a marathon runner. It proves that Commercial Off-The-Shelf (COTS) parts can go to space, but only if we accept the risk that they might die at any moment. For a $2.7 billion rover, that is a gamble NASA is not willing to take.

Conclusion: Different Worlds, Different Eyes

The battle of Automotive vs. Space LiDAR isn’t really a fair fight—it’s a clash of philosophies. On one side, we have companies like Luminar pushing the envelope of what is possible within the constraints of mass production and consumer budgets. Their goal is to make the technology affordable enough to put a self-driving car in every driveway. On the other side, we have NASA, pushing the envelope of physics to build machines that can endure the harshest environments known to man.

While the underlying science of bouncing lasers off objects is identical, the execution could not be more different. Automotive engineering is a race to optimize cost and scale; space engineering is a relentless pursuit of survival and reliability.

So, the next time you see a sleek autonomous vehicle navigating a rainy street, admire the technology for what it is. But remember why that same sensor isn’t cruising across Jezero Crater. Earth technology is designed to work most of the time for the lowest possible price. Mars technology is designed to work every single time, no matter the cost. When you are 140 million miles from the nearest repair shop, “good enough” simply isn’t an option.

Lascia un commento