Abstract: The Challenge of Martian Latency

The evolution of rover AI is driven by a fundamental engineering necessity: overcoming the communication latency between Earth and Mars.

This delay, which can exceed 20 minutes one-way, makes direct teleoperation (or “joysticking”) logistically impractical. Any command sent to avoid a hazard would arrive far too late.

This operational constraint imposes the critical need for onboard decision-making autonomy, transferring intelligence from the Earth-based operator to the rover’s software.

This article analyzes the architectural evolution of this artificial intelligence. The analysis traces the progression from purely reactive paradigms (the “bump and go” of Sojourner) to the cognitive and real-time predictive systems (the AutoNav of Perseverance).

The Genesis: Sojourner (Mars Pathfinder, 1997) – The Reactive Paradigm

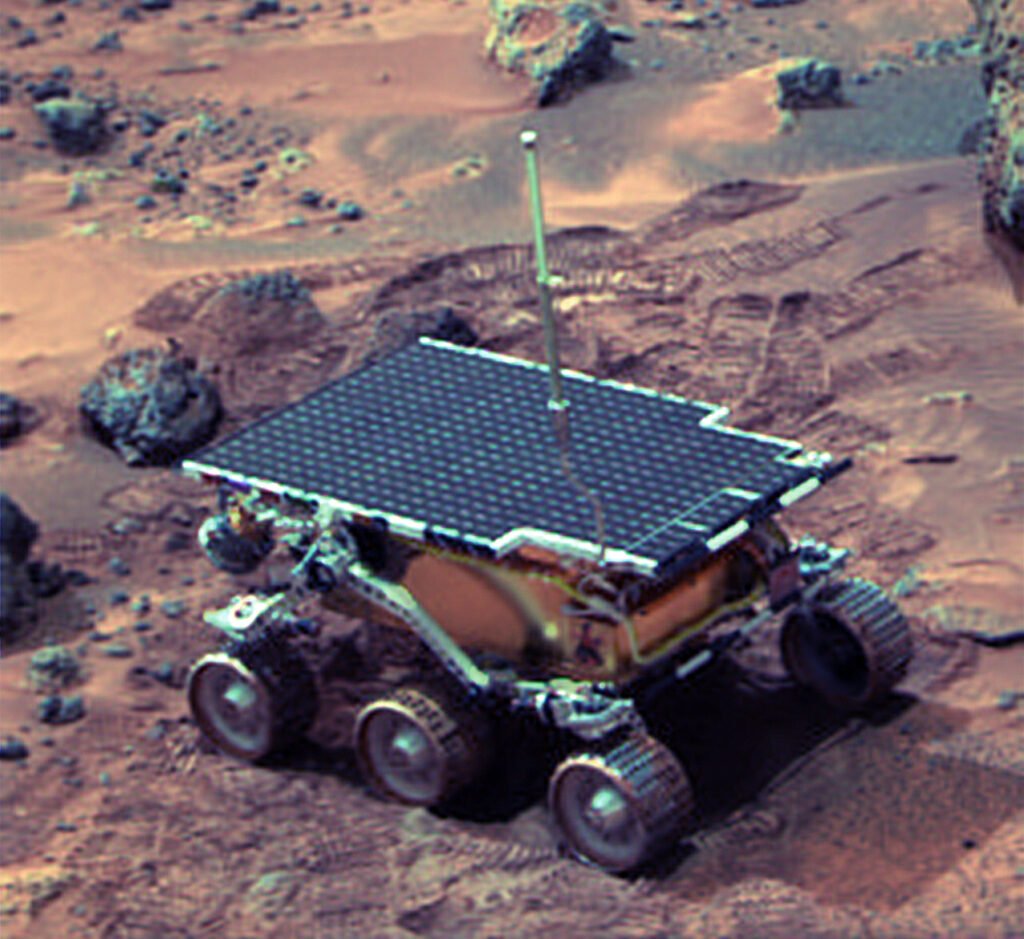

The 1997 Mars Pathfinder mission implemented the first true autonomous navigation system on Mars. Sojourner’s approach, however, was a purely reactive paradigm—an elegant system dictated by severe computational constraints and designed for a single purpose: survival.

The “Bump and Go” System: A Reactive Architecture

Sojourner’s software did not perform pathfinding, nor did it build maps. It operated on an immediate input-output logic focused exclusively on obstacle avoidance.

The methodology was based on laser stripers sensors. The rover projected five thin beams of non-coherent light onto the terrain ahead. Its cameras monitored the shape and continuity of these stripes.

If a laser stripe appeared “broken” (indicating a drop-off) or “deviated” (indicating a rock), the software registered a hazard event (“bump”). The subsequent action was pre-programmed and non-deliberative:

- Stop: Immediately halt forward motion.

- Turn: Pivot (rotate) in place by a predefined angle.

- Retry: Attempt to advance in the new direction.

This IF-THEN-ELSE cycle continued until the path was clear, giving rise to the name “Bump and Go.”

Hardware Constraints: Intel 80C85 CPU and Laser Sensors

This reactive strategy was a necessity imposed by the hardware. The “laser stripers” hardware consisted of laser diodes (850nm) paired with cameras equipped with narrow-band filters to isolate the reflected laser light from sunlight.

The “brain” was an 8-bit Intel 80C85 processor, a CMOS radiation-hardened (rad-hard) version designed to resist bit-flips caused by cosmic radiation, unlike commercial (COTS) processors.

This CPU, operating at approximately 100 KIPS (Kilo Instructions Per Second), was barely sufficient to manage the reactive cycle. It did not permit real-time map creation (like SLAM) or motion estimation via vision (Visual Odometry), resulting in a maximum speed of about 1 cm/s.

Taxonomic Analysis: Sojourner’s Reactive AI

A common error is to confuse the term “AI” exclusively with its modern incarnation (Machine Learning or Deep Learning). AI, as a field of study, includes a broad spectrum of systems.

Sojourner did not use machine learning; it had no “experience,” memory (maps), or predictive capability. It belonged to what robotics defines as a subsumption architecture (or reactive paradigm): a finite-state automaton based on fixed IF-THEN rules.

In summary: Yes, it was AI. It was a hard-coded intelligence designed to replace a human operator in a very low-level task (avoiding rocks), but it was not cognitive or learned intelligence.

The Intermediate Leap: Spirit & Opportunity (MER, 2004) – The Deliberative Era

The Mars Exploration Rovers (MER), Spirit and Opportunity, represented a quantum leap in the evolution of rover AI.

The paradigm shifted radically: from simply “avoiding obstacles” to “understanding the environment and actively planning.” This transition was made possible by a quantum leap in both computational hardware and perception algorithms.

The Introduction of Visual Odometry (VO)

For the first time, a Martian rover no longer relied exclusively on wheel odometry (counting wheel rotations) to determine its position. Wheel odometry is notoriously unreliable on Martian regolith due to slippage.

MER introduced Visual Odometry (VO). This algorithmic methodology uses stereoscopic navigation cameras (Navcams) to track visual features (like rocks, sand patterns) between sequential image frames.

By analyzing the apparent displacement of these features, the onboard software could calculate the rover’s translation and rotation (its 6-DoF pose) with high precision, actively correcting for errors induced by wheel slippage.

The Enabling Hardware: The RAD6000

This complex computer vision calculation was made possible by the RAD6000 processor, a radiation-hardened version of the PowerPC.

Operating at approximately 20 MIPS (Millions of Instructions Per Second), the RAD6000 provided sufficient computational power for stereo image processing—a task unthinkable for Sojourner’s hardware (approx. 0.1 MIPS).

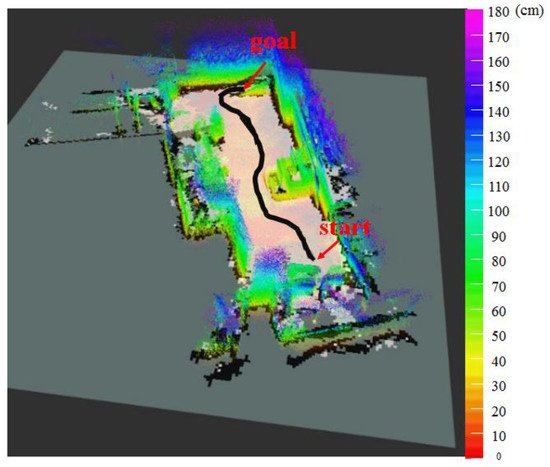

From “Bump” to “Think”: 2.5D Pathfinding

The most significant innovation of MER was the adoption of a deliberative (stop-and-think) navigation cycle, in stark contrast to Sojourner’s reactive approach.

The operational process was as follows:

- Stop: The rover would come to a complete halt.

- Acquire: The Navcams would acquire a new stereo pair of images of the terrain ahead.

- Model: The onboard software processed the images to generate a disparity map. This is not a full 3D model, but a 2.5D elevation map identifying the location and height (or distance) of obstacles.

- Plan: On this 2.5D map, a pathfinding algorithm (a variant of the A* algorithm) identified safe areas (“goodness map”) and calculated the optimal path for the next segment (typically 1-2 meters).

- Execute: The rover advanced along the calculated safe path.

- Repeat: The cycle would begin again.

This method, though slow, was extremely robust. It allowed the rover to safely navigate through complex rock fields that would have been impassable for a purely reactive system.

Technical Note (2.5D vs 3D): A 2.5D map (or “elevation grid”) is not a full 3D polygonal model. It is a 2D grid viewed from above (similar to a topographic map) where each cell $(x, y)$ is assigned an elevation value $z$. This was sufficient to identify slopes, obstacles (rocks), and pits (sand).

The Impact of MER’s “AutoNav” Software

This suite of capabilities was managed by the AutoNav software, developed and refined by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

The effectiveness of this deliberative system is proven by the mission’s results. Opportunity, designed for a 90-Sol (day) mission and a 600-meter traverse, operated for 14 years, traveling over 45 kilometers.

This distance record would have been inconceivable without AutoNav’s autonomy. The system handled tactical, meter-by-meter navigation, allowing human planners on Earth to focus on strategic scientific goals (long-term planning) rather than teleoperated guidance (joysticking) in real-time.

The Cognitive Shift: Curiosity (MSL, 2012) – The Advent of AutoNav

The Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), with its rover Curiosity, does not represent an incremental evolution from Spirit and Opportunity; it marks a true cognitive shift.

If the MER rovers had to stop to “think,” Curiosity introduces the era of continuous autonomous navigation. This is the prototype for the modern autonomy we see in Perseverance.

The leap was possible thanks to a fundamental hardware upgrade: the RAD750 processor. This CPU, a radiation-hardened version of the PowerPC 750, operates at approximately 200 MIPS, a ~10x increase in computational power over MER.

This computational surplus allowed for the implementation of the first true version of AutoNav.

AutoNav 1.0: Fusing Perception and Navigation

Curiosity’s breakthrough was the ability to drive while mapping the environment. The “stop-and-think” cycle was replaced by a “think-while-driving” cycle.

This was achieved by decoupling the perception hardware from the main CPU.

Dedicated Hardware Architecture: FPGAs

The JPL team implemented a hybrid hardware solution. While the RAD750 handled high-level decision-making (pathfinding, mission management), the stereo processing—the computational bottleneck—was delegated to FPGA (Field-Programmable Gate Arrays).

These chips, located within the rover, were custom-programmed to perform a single function incredibly efficiently: transforming stereo pairs from the Navcams into 3D disparity maps, in real-time.

This freed up the RAD750 CPU, allowing it to run the pathfinding algorithm on data that was continuously updated, even while the wheels were still in motion.

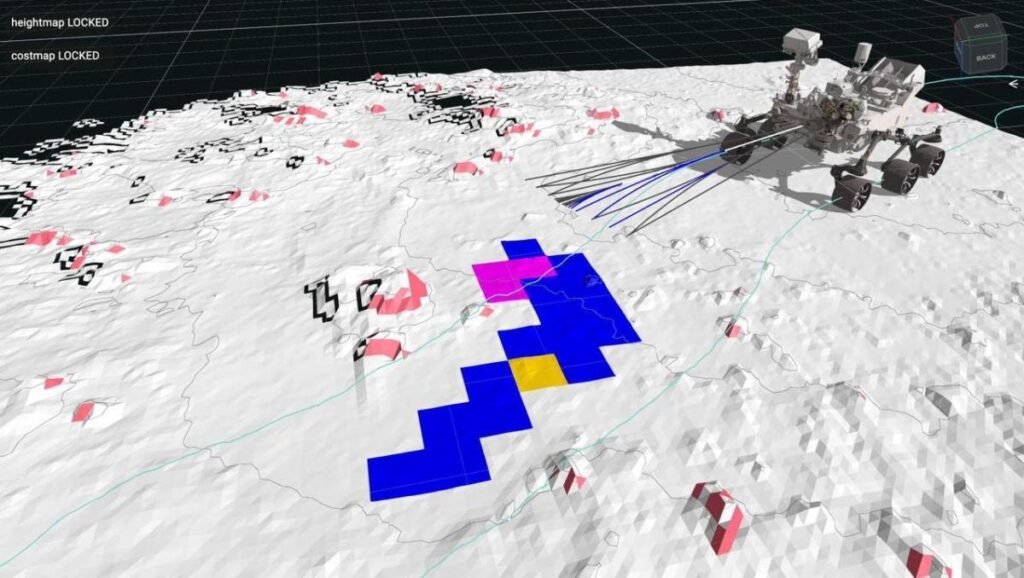

The Generation of Hazard Maps

Unlike the MER rovers, which generated 2.5D elevation maps, Curiosity’s AutoNav software builds Hazard Maps, also known as “goodness maps.”

The process is as follows:

- Stereo Processing (FPGA): The FPGAs generate a 3D point cloud of the terrain ahead.

- Terrain Classification: The software projects this 3D cloud onto a 2D overhead grid.

- Risk Analysis: For each grid cell, the system evaluates a “cost” or “risk” based on multiple factors:

- Slope (Tilt): Could the rover tip over?

- Roughness: Is the terrain too rugged and damaging to the wheels?

- Discrete Obstacles: Is there a rock present that exceeds the rover’s ground clearance?

- Areas are then classified binarily as “safe” (low-cost) or “unsafe” (high-cost or infinite-cost).

Algorithms: A* Pathfinding

On this constantly updated “goodness map,” AutoNav runs a pathfinding algorithm (typically A* or a variant like Field D*) to calculate the minimum-cost path.

The algorithm does not seek the shortest path in meters, but the safest path (the one that maximizes “goodness”) toward the local target. This allowed Curiosity to autonomously navigate for tens of meters at a time.

Focus on Wheel Damage and AutoNav Adaptation

While AutoNav was a revolution, its implementation on Curiosity was deliberately cautious. NASA could not risk a 2.5 billion dollar asset.

Curiosity’s autonomous driving speed was often software-limited to about 15-30 meters per hour. This “digital leash” ensured the rover always had enough time to identify a hazard (like a sharp rock, which became a serious problem for the rover’s wheels) and stop before impact.

Curiosity’s wheels were designed from aluminum, with a very thin “skin” (only 0.75 mm) to save mass. The design, with its “grousers” (v-shaped treads), was optimized for traction on sandy regolith.

However, Gale Crater proved to be a much harsher environment. The rover had to cross extensive fields of ventifacts: sharp, wind-carved rocks.

Around 2013-2014, images began to show alarming wear: significant cracks, holes, and tears in the wheel skins. This hardware damage forced JPL into a radical rethink of the navigation strategy. AutoNav’s autonomy no longer just had to find a “safe” path, it had to find a “gentle” path.

The team sent software patches to the rover to update the pathfinding algorithm (A*), making the “goodness map” analysis more sophisticated in avoiding pointed rocks.

The Pinnacle: Perseverance (Mars 2020) – Real-Time Predictive Autonomy

The Perseverance rover (Mars 2020) marks the current apex of Artificial Intelligence applied to planetary navigation. It surpasses Curiosity’s deliberative “think-while-driving” approach by introducing predictive and continuous real-time autonomy.

If Curiosity had to drive cautiously, Perseverance is designed to drive assertively. This transformation is enabled by a fundamental architectural upgrade that solves the computational bottleneck of its predecessors: AutoNav 2.0.

AutoNav 2.0: The “Vision Compute Element” (VCE)

Perseverance’s key hardware innovation is not an upgrade to its main CPU, which remains the proven RAD750, but the addition of the Vision Compute Element (VCE).

The VCE is a dedicated co-processor (a Xilinx Virtex-5 FPGA) designed exclusively for computer vision processing.

This dual-computer architecture introduces critical computational parallelism. The RAD750 handles high-level planning (A* pathfinding), while the VCE executes the entire vision pipeline (acquisition, Visual Odometry, stereo-correlation) independently and at high speed.

The result is transformative. AutoNav 2.0 never stops to think. Acquisition, processing, and planning occur in a continuous high-frequency (pipeline) cycle. This allows Perseverance to achieve sustained autonomous driving speeds of up to 120 meters per hour—an order of magnitude faster than Curiosity.

From 2D Mapping to 3D Modeling

The VCE doesn’t just allow the rover to do the same things faster; it allows it to do computationally different things. Perseverance generates high-density 3D polygonal models (meshes) of the terrain ahead, in real-time.

The VCE can process images from the stereo Navcams to generate 3D maps with millions of points (up to 6.5 million polygons) for each planning “step.”

This 3D representation allows for a much more sophisticated traversability assessment. The software no longer just asks “is it flat?” but “is this 25cm rock climbable or is it a 35cm obstacle that must be routed around?”

The Role of Terrain Relative Navigation (TRN)

While AutoNav handles surface navigation (driving), the most revolutionary AI innovation of Mars 2020 was arguably the Terrain Relative Navigation (TRN), used during the critical Entry, Descent, and Landing (EDL) phase.

TRN allowed the rover to “see” the terrain during its final descent. The onboard AI compared real-time images from the (Lander Vision System) camera with an orbital database map.

By identifying known landmarks, the TRN determined the rover’s exact position (autonomous localization) and actively corrected the descent trajectory to land in a pre-selected safe target. This system avoided the hazards of Jezero Crater in seconds, with no human intervention.

Analytical Consideration: Perseverance’s AI

A critical analysis of Perseverance’s AI must start from a fundamental premise: it is not a 2024 AI, but a triumph of resource-constrained engineering with hardware specifications defined around 2015.

The common mistake is to compare its performance to COTS (Commercial Off-The-Shelf) terrestrial systems, which run on power-hungry, modern GPU architectures. Perseverance’s AI operates on the RAD750 processor, a Rad-Hard PowerPC architecture whose origins date back to the late 1990s.

This choice is not dictated by obsolescence, but by robustness. This hardware is proven to survive launch vibrations, extreme temperatures, and the constant bombardment of cosmic radiation.

The human role (such as citizen science to train models, e.g., AI4Mars) does not show a weakness in the AI. On the contrary, it defines its function: Perseverance’s AI masterfully handles tactical autonomy (the “how” to drive safely meter-by-meter), while humans on Earth, separated by a 20-minute latency, manage strategic supervision (the “why” to go to a location).

Comparative Analysis: The Evolution in Numbers

The aggregate analysis of the four generations of Martian rovers reveals that the quantum leaps in autonomy are directly correlated with the increase in onboard computing power and, most importantly, hardware specialization (co-processing).

| Mission (Rover) | Computational Architecture | Power (MIPS) | AI Paradigm (Navigation) | Max. Autonomous Speed |

| Sojourner (1997) | Intel 80C85 (Rad-Hard) | ~0.1 MIPS | Reactive (Behaviour-Based) | ~1 cm/s |

| Spirit/Oppy (MER, 2004) | BAE RAD6000 | ~20 MIPS | Deliberative (Stop-and-Think) | ~5 cm/s (In segments) |

| Curiosity (MSL, 2012) | BAE RAD750 (+ FPGA) | ~200 MIPS | Parallel Autonomy (Think-while-Driving) | ~4 cm/s (Cautious) |

| Perseverance (M2020, 2021) | BAE RAD750 + VCE | ~200 MIPS (CPU) | Predictive Autonomy (Real-Time SLAM) | ~12 cm/s (Cruise) |

Conclusion: Beyond AutoNav – The Future of Autonomous Exploration

The analysis of the evolution of rover AI from 1997 to today demonstrates a clear transition: from hardware-constrained reactive systems to predictive systems enabled by specialized co-processors.

However, the next frontier for autonomy is no longer just about movement, but about scientific decision-making.

From “Where to Drive” to “What to Analyze”: Scientific AI (AEGIS)

The true paradigm shift has already begun with systems like AEGIS (Autonomous Exploration for Gathering Increased Science). This software, implemented on both Curiosity and Perseverance, acts as a “scientific brain” complementary to AutoNav.

While AutoNav decides how to reach a destination, AEGIS analyzes terrain images and autonomously identifies scientific targets (rocks with unique geological shapes, albedo, or colors) worthy of in-depth analysis.

AEGIS can then target instruments like the SuperCam for a laser (LIBS) analysis, all without waiting for a command cycle from Earth. The AI is transitioning from “driver” to “field scientist.”

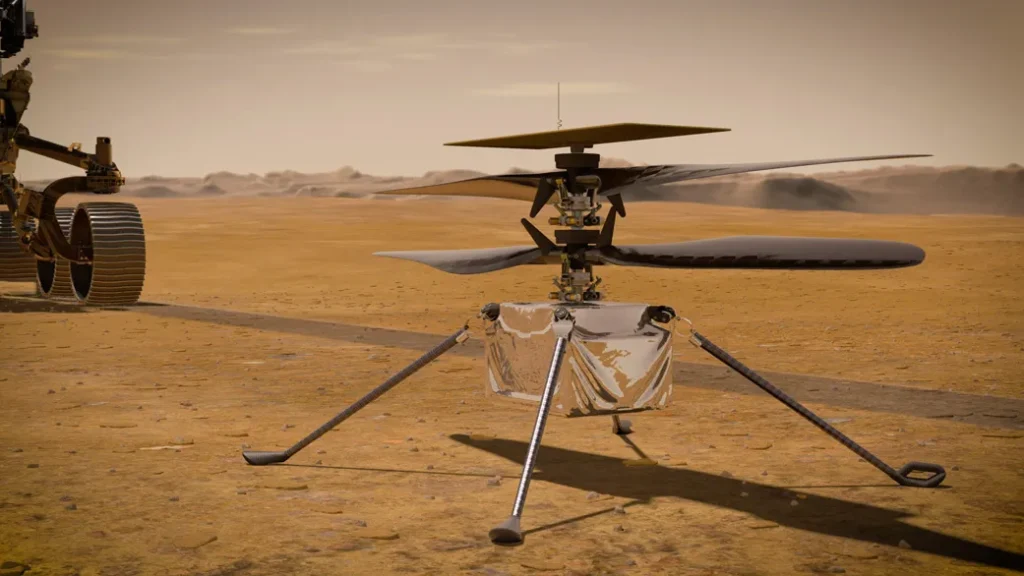

The Next Frontier: SLAM and the COTS vs. Rad-Hard Dilemma

The future of autonomous exploration will require navigation in unknown and GPS-denied environments for which AutoNav was not designed, such as Martian lava tubes or the subsurface oceans of Europa.

The algorithmic solution is SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping), where the rover builds a persistent 3D map and localizes itself within it in real-time. This, however, requires computational power that the current Rad-Hard architecture struggles to provide.

Herein lies the hardware challenge of the next decade:

- Reliability (Rad-Hard): Continue with reliable but slow CPUs like the RAD750, which limit AI complexity.

- Performance (COTS): Adopt COTS (Commercial Off-The-Shelf) processors, like the Snapdragon 801 used successfully on the Ingenuity helicopter. These chips are orders of magnitude faster but extremely vulnerable to radiation and have a much lower Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF).

The success of Ingenuity has proven that a hybrid architecture is possible. The future will not be a choice between COTS or Rad-Hard, but a complex integration of the two.

The evolution of rover AI is not over; it is just entering its most critical phase. Future missions, like Mars Sample Return, will depend not just on how far a rover can drive, but on how “intelligently” it can perceive, decide, and act in total autonomy.

This article analyzed the historical trajectory of Martian autonomy. But what exactly are the pathfinding algorithms these rovers use? Continue following us as we analyze A*, D* Lite, and the algorithms that allow Perseverance to choose its path.

Lascia un commento